Alcoa’s Huntly Mine sprawls for miles across Western Australia’s Northern Jarrah Forest as seen from an airplane on March 25, 2025. The company’s mining lease covers nearly 5,000 square miles, and Alcoa is seeking an expansion to mine deeper into the forest.

Since 1963, Alcoa has mined the foothills of Australia’s Darling Range under a special political agreement that skirts regulation, guarantees access to scarce water and assures low royalty rates. What was once a modest operation has become one of the world’s most expansive. Australian ore now generates about three-quarters of Alcoa’s total production of alumina — an oxide refined from bauxite and smelted into aluminum to make smartphones, computers, skyscrapers, electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines. Now, the Pittsburgh metal maker seeks more to keep up with demand — to build, Alcoa says, the green energy future

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations’ chief climate body, declared the Northern Jarrah Forest critically endangered by a warming world. Alcoa’s lease, spanning nearly 5,000 square miles, cuts across much of the remaining forest, with over 8,000 unique plant and animal species. The company has long said it effectively rehabilitates the forest that it clears, producing company-sponsored research to back its claims. But mining, independent scientists say, threatens to push the forest over the edge. If more is lost, the entire ecosystem could collapse.

Western Australian authorities have warned that if Alcoa is allowed to expand, contamination of drinking water for the city of Perth, and its population of 2.3 million, is “considered certain,” and could endanger water quality in “most, if not all,” of Perth’s drinking water dams. Now, the company seeks approval for its biggest expansion to date.

While residents are quick to point to the jobs the company has employed for generations, they are also steadfast that Alcoa’s local legacy — mountains of red residual sludge totaling nearly 100 billion gallons — will remain far longer than the Americans do. Retaining walls holding tens of billion gallons of waste reportedly failed to be certified as stable during recent tests, stoking concern about the possibility of a breach.

Botanist Kingsley Dixon inspects a 500-year-old kingia australis, an ancient plant endemic to Western Australia, in unmined forest near an Alcoa mine site in Waroona on March 23, 2025.

“Two things want bauxite: The Aluminum Company of America and the jarrah forest. They both have an utter, total dependence on it. Who wins?” questioned Dixon.

A dump truck waits in the distance at a site in Alcoa’s Willowdale Mine complex on March 22, 2025. The company extracts bauxite from a layer of ore about 10-15 feet beneath the forest floor using explosives and heavy machinery.

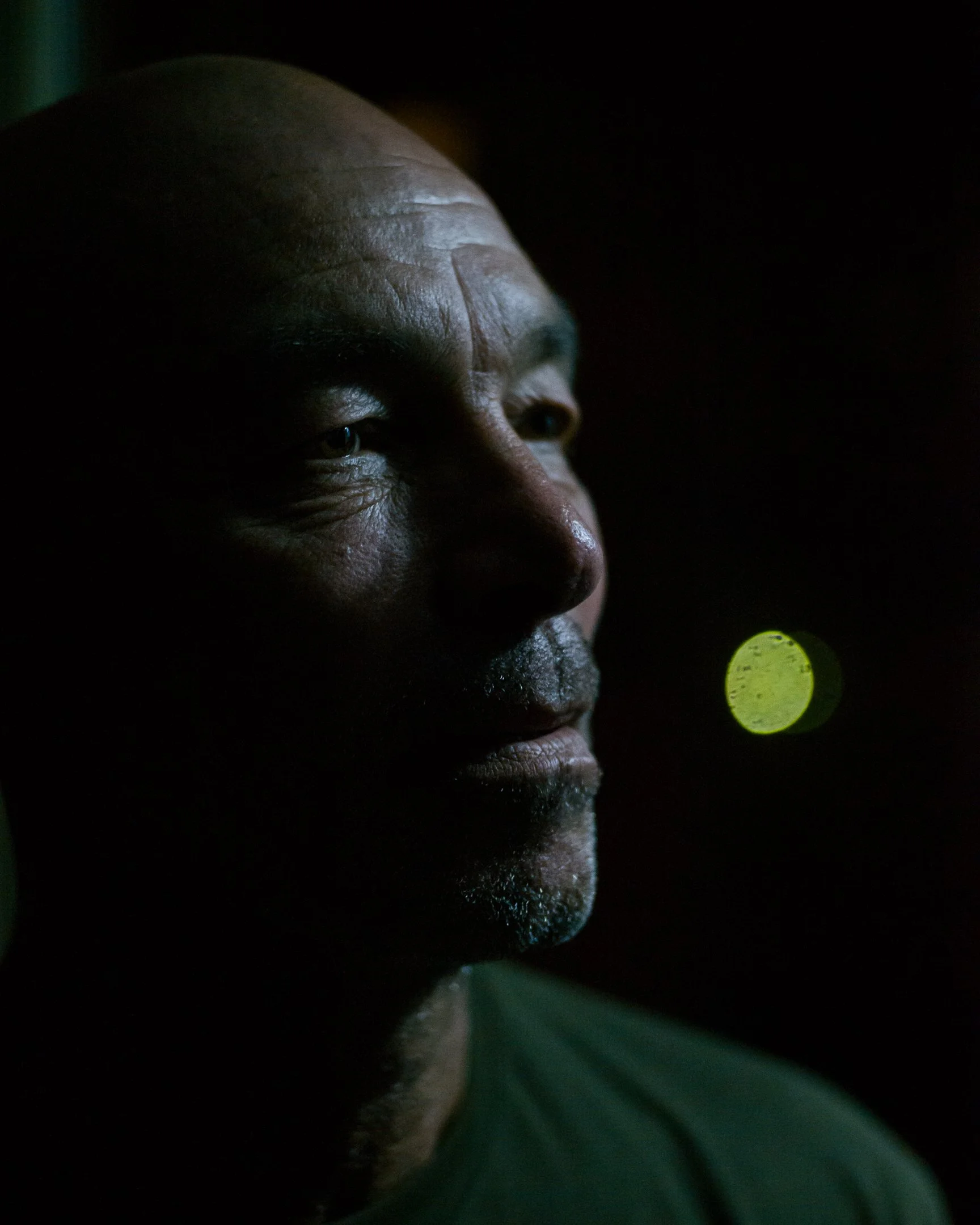

Cheryl Martin, a member of the First Nation Noongar people, rubs dust between her palms at the bank of the Murray River in Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 28, 2025. The riverbank is the site of an 1834 massacre where as many as 80 Noongar people were slain by colonists, and which Martin’s great-great-great-grandmother survived.

Christopher Nannup (left) skins a kangaroo during a hunt at a a reserve near Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 24, 2025. Nannup and his family are part of a local Noongar corporation that recently acquired the rights to occupy and manage the land.

Kingsley Dixon drives his Toyota Hilux through a former mine site near Alcoa’s Willowdale Mine in Western Australia on March 23, 2025. Last year, Dixon published new research that found Alcoa’s rehabilitated mine sites lacked the biodiversity that defines unmined jarrah. Crucial plant species were “effectively absent,” and replanted forest would not sustain key animal species. The reason, the research posited, could be the removal of the bauxite on which the ecosystem evolved.

(Left) A conveyor transports bauxite from Alcoa’s forest mines to the company’s refineries near the coast on March 14, 2025. (Right) A roadside jarrah tree near Pinjarra on March 21, 2025.

Dean Autherell, founder of the Carnaby’s Crusaders, holds a black cockatoo at his home rescue center north of Perth, Western Australia, on March 25, 2025. Autherell constructs large wooden boxes that he attaches to trees to create artificial nesting sites for the black cockatoo, an endangered endemic species threatened by increased forest mining. “This is just a Band-Aid — it’s not a long-term solution. The only long-term solution is restoring the habitat,” he said.

George Walley, a Noongar elder, inscribes his name beneath a bridge on the outskirts of Pinjarra on March 24, 2025. The bridge has become an unofficial monument for local First Nations people.

Retaining walls hold tens of billions of gallons of waste at an Alcoa storage site on the outskirts of Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 25, 2025. The piles are some 150-feet tall, and residents say winds whip the residue into clouds of red dust that reach homes and lungs for miles.

Richard Sheridan writes his initials in the red dust that blankets his property near Alcoa’s red mud lakes on March 15, 2025. Since 2003, Sheridan, his wife, Collette, and their three children have experienced a range of symptoms they blame on exposure to the dust, including frequent nosebleeds, migraines, breathing difficulties and hair loss. Lab testing showed dioxins in their blood, they said, and recent urine and hair samples revealed a slew of toxic heavy metals.

(Left) Collette Sheridan stands at the property where she lives with her husband, Richard, and which borders Alcoa’s residue lakes in Pinjarra on March 15, 2025. (Right) Collette Sheridan’s palm after cleaning dust in the chalets she and her husband built on the property on March 20, 2025.

The annual Pinjarra Cup, a horse race held at a track sponsored by Alcoa, occurs just outside the company’s property in Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 23, 2025.

Franklin Nannup (left) and his nephew, Christopher Nannup (center), fish for mullet with relatives at a reserve on the outskirts of Alcoa’s mining lease, near Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 24, 2025. “I’m going to be opposing [Alcoa’s planned expansion] all the time for the simple fact that there’s only one place in the world where the jarrah trees grow — and that’s my country,” said Franklin Nannup.

(Left) Former Alcoa worker Dave Puzey photographed at home in Binningup, Western Australia, on March 27, 2025. Puzey experienced long bouts of extreme lethargy a few years into his 11-year stint at Alcoa in addition to chronic respiratory illness and debilitating chemical sensitivity, all of which gradually worsened, he said. (Right) Alcoa’s Wagerup refinery, near Yarloop, Western Australia, on March 16, 2025.

An excavator moves debris at Alcoa’s Huntly Mine near Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 28, 2025.

Unmined jarrah forest near Dwellingup, Western Australia, on March 26, 2025.

George Walley, a local Noongar elder, sits at the edge of Alcoa’s Huntly Mine, near Pinjarra, Western Australia, on March 24, 2025. “The bauxite mining activity is taking from Mother Earth … from what is ours,” said Walley.